Designing a Purely Functional Data Structure

Functional programming nicely leverages constraints on how programs are written thereby promoting a clean and easy to reason about coding style. Purely functional data structures are (surprisingly) built out of those constraints. They are persistent (FP implies that both old and new versions of an updated object are available) and backed by immutable objects (FP doesn’t support destructive updates). Needless to say, it’s a challenge to design a purely functional data structure that meets performance requirements of its imperative sibling. Fortunately, it’s quite possible in most of the cases, even for those data structures whose reference implementations are backed by mutable arrays. This post precisely describes a process of designing a purely functional implementation technique for Standard Binary Heaps, with the same asymptotic bounds as in an imperative setting.

Immutability and Persistence

Immutability and persistent are quite similar terms, which often substitute each other. We say immutable vector (in Scala) but mean persistent vector (in Clojure): both implementations are based on the same abstract data structure Bit-Mapped Vector Trie but named differently. Although, there is a slight difference between immutability and persistence as they apply to data structures.

- Persistent data structures support multiple versions

- Immutable data structures aren’t changeable

The difference between immutable and persistent data structures in how they handle updates. A persistent data structure handles updates in a smart and memory-efficient way in order to keep its previous version unchanged, while an immutable data structure simply doesn’t care about updates at all (for example, Guava’s ImmutableList doesn’t even support updates), since its previous version could be destroyed.

The following example demonstrates the difference between Guava’s ImmutableList and Scala’s persistent List in terms of memory footprint (smart updates vs. dumb updates).

// xs takes O(n) memory

val xs = ImmutableList.of(1, 2, 3)

// yx takes O(n) memory

val ys = 1 :: 2 :: 3 :: Nil

// dumb update: xxs takes O(n) memory (full copying)

val xxs = ImmutableList.builder.add(0).addAll(xs).build()

// smart update: yys takes O(1) memory (structural sharing)

val yyx = 0 :: yxPurely Functional Data Structures

Purely functional data structures are always persistent, which means they handle updates in a memory-efficient way. This achieved by an implementation technique called structural sharing. A persistent data structure shares its internal structure between its versions, which is completely safe to do, since none of the versions can ever be changed or destroyed.

val xs = 1 :: 2 :: 3 :: Nil

val xxs = 0 :: xs // shares (not copies) the tail with xsAnother heavily used implementation technique is path copying. It often requires to make some deep changes in a persistent data structure (i.e., insert, delete or update an element). To do so, we simply copy its nested structures (persistent data structures are often backed by ADTs) along the path to an element being modified. Both path copying and structural sharing aim to minimize the cost of modifying a persistent data structure: everything that can’t be shared (via structural sharing) is copied (via path copying).

def concat[A](xs: List[A], ys: List[A]): List[A] =

if (xs.isEmpty) ys

else xs.head :: concat(xs.tail, ys) // copies the path to ysPath copying is a quite lightweight operation that usually takes less than O(n) time to perform. Although, there are plenty of specialized data structures highly optimized for a concrete operation to make it in an amortized constant time (with no path copying). For example, Fast Mergeable Integer Maps and Persistent Catenable Lists support constant time merge and concat operations correspondingly.

Purely Functional Heaps

Tree-based data structures (i.e., trees, heaps and tries) are considered as low-hanging fruits for a functional setting, since they map directly to Algebraic Data Types. At the first approximation, a typical functional implementation of a persistent tree looks as follows.

sealed trait Tree[+A] { def value: A }

case class Branch[+A](value: A, left: Tree[A], right: Tree[A]) extends Tree[A]

case object Leaf extends Tree[Nothing]There are several purely functional implementations of heaps such as Leftist Heap, Skew Heap and Pairing Heap with good asymptotic bounds. Although, there are other heaps without proper functional implementations. The simplest of them are Standard Binary Heaps, which do not fit well into a functional environment since their reference implementation is backed by mutable arrays. Luckily, it’s quite possible bring them into a purely functional world.

Standard Binary Heap

A binary heap (Williams, 1964) is a data structure that implements a priority queue interface and guarantees logarithmic running time for insert, delete operations and constant time access to minimum/maximum element. Binary heaps are commonly viewed as binary trees which satisfy two invariants:

- The shape invariant: the tree is a complete binary tree.

- The min-heap invariant: each node is less than or equal to each of its children.

In Scala a binary min heap might be represented as abstract Heap class with two variants: Branch and Leaf.

sealed trait Heap[+A] {

def min: A

def left: Heap[A]

def right: Heap[A]

def isEmpty: Boolean

// Both 'size' and 'height' are stored in each node.

val size: Int

val height: Int

}

case object Leaf extends Heap[Nothing] {

val size: Int = 0

val height: Int = 0

def isEmpty: Boolean = true

}

case class Branch[+A](min: A, left: Heap[A] = Leaf, right: Heap[A] = Leaf) extends Heap[A] {

def isEmpty: Boolean = false

val size: Int = left.size + right.size + 1

val height: Int = math.max(left.height, right.height) + 1

}Note that the height of a heap is defined as max height of its children plus one, while tge size of a heap is defined as the sum of its children sizes plus one; and both are calculated only once in a heap constructor. Also, to simplify calculations, suppose that singleton heap’s height is 1.

Except for height and size operations, this signature looks like a classic functional implementation of a Binary Search Tree. The two new operations are actually accessors to new fields in a heap - its height and size. These additional data should be accessible in constant time to define an efficient and simple search criterion for insert and remove operations.

Insertion in O(log n)

Insertion into a functional binary heap must not violate either of its invariants - neither the shape invariant nor the min-heap invariant. For this purpose two problems should be solved. First, to maintain the shape invariant a new node should be inserted in the first empty spot at the last level of the heap. Second, to maintain the min-heap invariant the inserted node should be bubbled up to the heap root until it becomes greater than its parent.

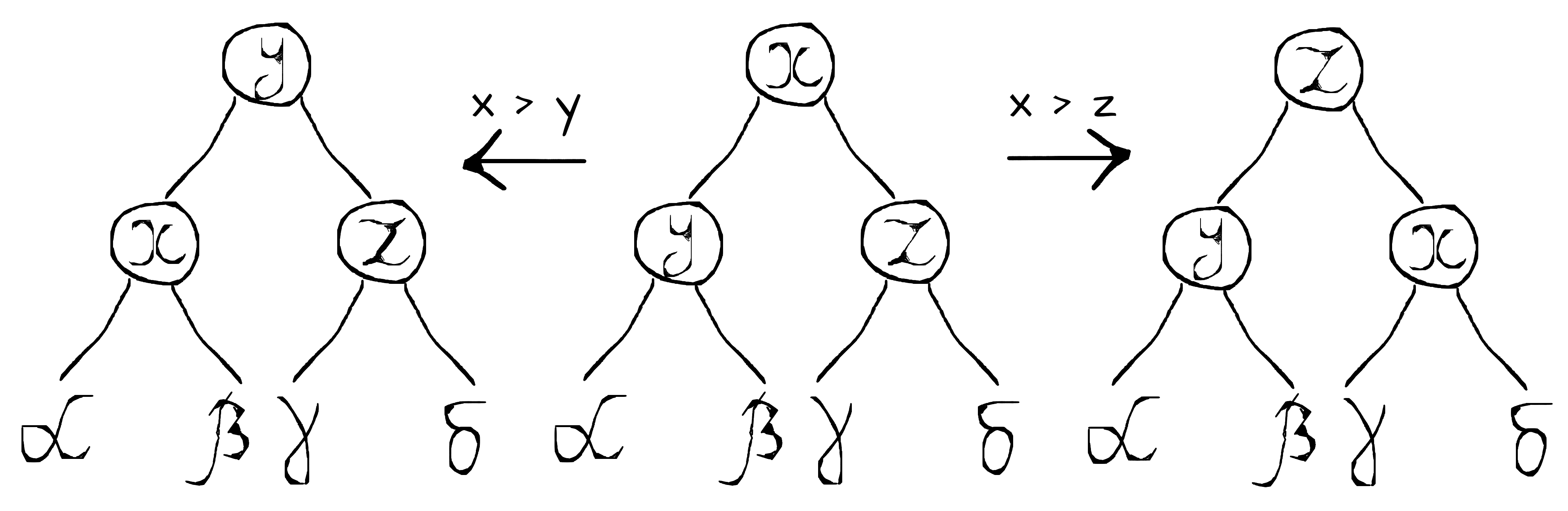

Bubbling up is quite a simple transformation that can be done at each level in constant time. There are two cases depending on whether the violation is at the left or right child (see “Figure 1” above). In either case the violation should be fixed by swapping two nodes - the root node and the child that violates the min-heap invariant. There is also a third case, when it doesn’t violate anything. In this case, a heap should be simply rebuilt with given parameters. In other words, all affected nodes should be copied in order to maintain data structure persistence. More precisely, bubbleUp and insert operations might be defined as follows.

def bubbleUp[B : Ordering](x: B, l: Heap[B], r: Heap[B]): Heap[B] = {

val ordering = Ordering[B]; import ordering._

(l, r) match {

case (Branch(y, lt, rt), _) if (x > y) =>

Branch(y, Branch(x, lt, rt), r)

case (_, Branch(z, lt, rt)) if (x > z) =>

Branch(z, l, Branch(x, lt, rt))

case (_, _) =>

Branch(x, l, r)

}

}

def insert[B >: A : Ordering](x: B): Heap[B] =

if (isEmpty) Branch(x)

else if (???) bubbleUp(min, left, right.insert(x))

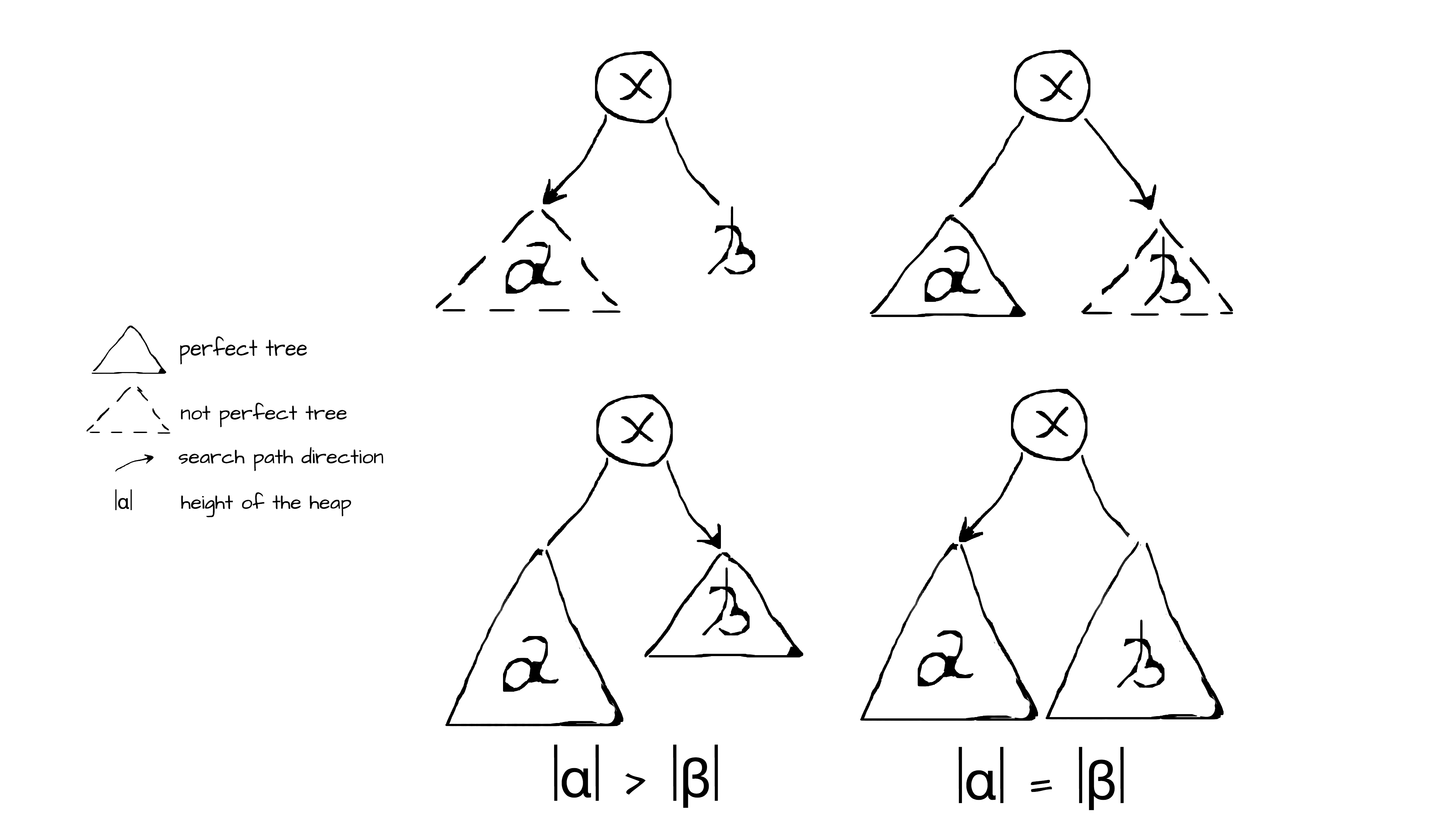

else bubbleUp(min, left.insert(x), right)The last thing to discuss is how to find a proper spot for a new node. The algorithm is based on a simple idea that binary heap will always be a complete tree if it tends to be a perfect tree each time it’s modified. There are two definitions of perfect trees: mathematical and recursive. Mathematical definition: a perfect binary tree contains 2^(h+1) − 1 nodes, where h is the height of the tree. Recursive definition: a tree is perfect if its children are perfect trees of the same height. Combining these facts together, one can define search criteria which allow filling a heap level by level from left to right, thereby maintaining the shape invariant. In other words, new nodes should be inserted in such a way as to make the heap be a perfect tree. This can be simply achieved by the following requirements of the recursive definition, using the math definition as an efficient test on tree perfectness. Thus, the search criteria for insertion consist of four cases depending on whether the children are perfect trees and whether their heights are equal.

The straightforward implementation of this idea (see “Figure 2” above) with four cases looks as follows.

def insert[B >: A : Ordering](x: B): Heap[B] =

if (isEmpty) Heap(x)

else if (left.size < math.pow(2, left.height) - 1)

bubbleUp(min, left.insert(x), right)

else if (right.size < math.pow(2, right.height) - 1)

bubbleUp(min, left, right.insert(x))

else if (right.height < left.height)

bubbleUp(min, left, right.insert(x))

else bubbleUp(min, left.insert(x), right)The insert operation performs two traversals along the search path of a heap. First, in a top-down manner it searches for the first empty spot in a heap thereby maintaining the shape invariant. Second, it rebuilds the affected nodes of a heap in a bottom-up manner thereby maintaining the min-heap invariant. Both traversal take less than O(log n), since the longest possible path for perfect trees is log n. Thus, the time complexity of insertion is O(log n).

Conclusion

The most exciting thing about purely functional data structures is that there is always room for new ideas and techniques. Even today, this direction still attracts researches and enthusiasts of functional programming. It’s been 15 years, since Okasaki and the field is still developing: modern languages like Scala require modern and efficient data structures with optimal purely functional implementations.

The heap implementation in this post is based on a paper A Functional Approach for Standard Binary Heaps, 2013. The full source code (including operations remove and heapify) is available on Github.